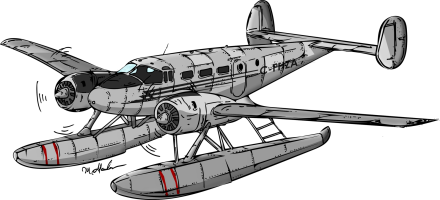

Arrival at the dock of Northwest Flying Inc. Beech 18 C-FKNL

Posted on YouTube by Jan Koppen

Nestor Falls, Ontario, Canada, June 2013.

The video is a visual and auditory record of a Beechcraft Model 18 floatplane arriving at its base of operations at Northwest Flying Inc.

- Aircraft: The subject is the twin-engine Beech 18 floatplane, registered as C-FKNL.

- Setting: The action takes place on a body of water, likely at the floatplane base in Nestor Falls, Ontario (consistent with other videos on this channel), which is surrounded by forest.

- Focus: The video captures the sequence from the aircraft’s final movements on the water to its secure position at the dock.

The content typically follows these stages of a floatplane arrival:

Water Taxi: The aircraft is seen already on the water, moving under power, with the distinctive sound of its radial engines clearly audible. The speed is slow and controlled, reducing the splash as it heads towards the dock.

Maneuvering: The pilot skillfully maneuvers the large aircraft into a suitable position to approach the narrow dock area. This often involves reducing power, using the engines differentially to steer, and fighting any wind or water currents.

Docking: The final moments of the video would show the aircraft nearing the dock. Typically, ground crew or people waiting on the dock use ropes or grab the floats to gently bring the plane to a complete stop and secure it to the mooring structure.

The Sound That Changed Everything: Sitting in the Right Seat of a Beech 18

The first time I heard those twin Pratt & Whitney R-985 radial engines fire up, I was eight years old. My dad had just strapped me into the right seat—the co-pilot seat—of C-FKNL, the Beech 18 floatplane that would carry us to our fishing trip. My grandfather sat behind me with my dad, both grinning. He’d made this same flight with his father in 1963. Now it was my turn.

I didn’t know then that I was sitting in a piece of aviation history. I just knew the sound was the coolest thing I’d ever heard.

What Makes the Beech 18 Special?

The Beechcraft Model 18—everyone calls it the “Twin Beech”—isn’t just another old airplane. It’s one of the most successful aircraft ever built, with over 9,000 made between 1937 and 1969. That’s 32 years of production across 32 different versions.

Here’s why it matters:

The Beech 18 was built for reliability. During World War II, the military version (called the C-45) trained thousands of pilots and carried cargo and passengers across every theater of war. After the war ended, thousands of these military planes were sold cheap to civilian operators. Bush pilots in Canada saw the potential immediately.

What they got:

- Two powerful radial engines (450 horsepower each)

- Tough construction that could handle rough conditions

- Room for 6 people with cargo

- Ability to land on short, rough strips

But the real genius was converting them to floats. Put this already-rugged airplane on pontoons, and suddenly you could reach any lake in Canada. No runway needed.

Why C-FKNL Became My Favorite Airplane

The specific Beech 18 I flew in—registration C-FKNL—is a C-45G model. The “G” variant was one of the military transport versions. After its military service ended, someone converted it to floats and brought it north to Ontario.

By the time I climbed aboard in 2013, C-FKNL had been working for Northwest Flying Inc. out of Nestor Falls for years. It was hauling fishermen, supplies, and families like mine to remote lakes all summer long, seven days a week.

The numbers that mattered to eight-year-old me:

- Two engines: If one quit, you still had one (this impressed me greatly)

- 450 horsepower per engine: More power than any car I knew

- 130 mph cruise speed: Faster than driving, way cooler than a car

- 8,725 pound takeoff weight: This thing was heavy but still flew

The number that matters now: C-FKNL was built in the 1940s or 1950s. It’s been flying for 70+ years. Most things built that long ago are in museums. This airplane still works for a living.

What It’s Actually Like to Fly in the Co-Pilot Seat

My dad let me sit in the front seat beside the pilot, just as grandpa did for him when he was a kid. In the bush plane world, if there’s room, you can sit up front. No special skill needed.

What I remember:

The instrument panel looked ancient compared to modern planes, but everything worked. Mechanical gauges with needles. Toggle switches that clicked solidly. A control yoke (the steering wheel) that actually moved cables running through the wings and tail.

The engines started with a cough and a puff of blue smoke, then settled into a rumbling idle that shook the entire airplane. Not hard—more like a heartbeat you could feel through the seat.

Taxiing on the water felt weird. The floats sat deep, creating drag, so you needed more power than you’d expect. The pilot used the engines to steer—more power on the left engine made us turn right, more power on the right engine made us turn left. (that was so cool)

The takeoff was the best part. The pilot pushed both throttles forward, and the sound changed from a rumble to a roar. The floats threw massive sprays of water on both sides. We accelerated slowly at first—that 9,000 pounds of airplane, fuel, people, and gear doesn’t jump out of the water quickly.

But then the floats “got on step” (rose up and started planing across the surface instead of plowing through it), the acceleration picked up, and suddenly we were airborne. The transition from water to air was smooth—one moment skipping across the lake, the next moment climbing away with the floats dripping water that caught the sunlight.

The flight itself lasted maybe 20 minutes. We cruised at about 130 mph, low enough to see individual trees and lakes. Grandpa pointed out landmarks from his own trips decades earlier—a distinctive rock formation, a burned area from a recent forest fire, a narrow channel between two lakes.

How They Keep 70-Year-Old Airplanes Safe

This is the part that matters most, even though eight-year-old me didn’t appreciate it.

Northwest Flying Inc. doesn’t treat their Beech 18s like antiques. They treat them like working aircraft that need to be absolutely reliable. Here’s how:

They Have Their Own Maintenance Hangar

Right at the Nestor Falls base, Northwest Flying has a full maintenance hangar. This isn’t a storage building—it’s a working shop where their dedicated Aircraft Maintenance Engineer (AME) can do everything from routine inspections to major repairs.

Why this matters: When your airplane base is hours from the nearest city, you can’t just call a mechanic when something breaks. You need the tools, parts, and expertise on-site. Northwest Flying has all three.

One AME for Five Airplanes

Most flight operations have mechanics who work on dozens of different aircraft. Northwest Flying’s AME focuses on just five planes: two Beech 18s, two DeHavilland Beavers, and one Cessna 180.

The advantage: This guy knows these specific airplanes intimately. He knows their quirks, their history, which components were replaced when, and what to watch for. The sources say he “takes exceptional pride in maintaining the fleet.” That’s not marketing language—that’s how small operations survive all these decades. If these planes don’t fly reliably, the business fails.

The Pilots Are Seriously Experienced

The pilots flying C-FKNL aren’t recent flight school graduates building hours. They’re described as “some of the most experienced bush pilots in the country,” many of whom have been with Northwest Flying for years.

Why experience matters in bush flying:

Bush flying is different from airline flying. You’re landing on water that might have floating logs. You’re dealing with wind that bounces off surrounding hills. You’re operating from remote lakes where the nearest help is a radio call and a long flight away. You need pilots who’ve seen thousands of these landings and know how to read conditions.

The pilot—who flew C-FKNL that day—had been flying for Northwest Flying since the early 1990s. His father had flown the same routes in the 1970s and 1980s before the family bought the business in 1987.

Generations of pilots in the same operation means:

- Knowledge gets passed down directly

- Younger pilots learn from actual experience, not just books

- The culture prioritizes safety because everyone knows everyone

The Pope Family History

The Pope family has run Northwest Flying Inc. since 1987, but their connection goes back further. Jack Pope (current owner Shane Pope’s father) started working there in the early 1970s as chief pilot before buying the business.

Shane Pope—who now owns and operates Northwest Flying—literally grew up around these airplanes. He said in an interview: “First job was pretty easy to get. Luckily, my dad hired me and uh the rest is history.”

What this family continuity creates:

When the same family runs an operation for 50+ years, safety isn’t an abstract corporate value. It’s personal. These pilots are flying their own family members, their neighbors’ kids, and repeat customers they’ve known for decades.

His family describe Shane as someone “who has found what he has always dreamt of doing and loves doing it.” That passion shows up in maintenance standards, pilot training, and daily operations.

Why the Beech 18 Is Perfect for This Work

After that first flight in 2013, I became obsessed with the Beech 18. I read everything I could find about why bush operators loved this airplane. Here’s what I learned:

Twin Engines Mean Safety Over Water

When you’re flying over lakes and forest with no emergency landing spots, having two engines matters enormously. If one engine fails on a Beech 18, the other engine can keep you flying long enough to reach a suitable lake.

Single-engine floatplanes are common in the bush, but for commercial passenger operations carrying families, the twin-engine safety margin makes sense.

Radial Engines Are Incredibly Reliable

The Pratt & Whitney R-985 radial engines in C-FKNL are air-cooled, nine-cylinder engines that were designed in the 1930s. They’re simple, proven, and repairable. Parts are still available because so many were built (over 40,000 R-985 engines were manufactured).

What “radial” means: The cylinders are arranged in a circle around the crankshaft, like spokes on a wheel. This design cools well (important when you’re running hard in hot weather) and tolerates rough handling.

Bush pilots love radial engines because they’re hard to break and relatively easy to fix. Modern turbine engines are more powerful and efficient, but they’re also more complex and expensive to maintain.

The Airframe Is Overbuilt

The Beech 18 was designed in an era when engineers didn’t have computer modeling to optimize every component. They built things strong—probably stronger than necessary by modern standards.

The result: These airframes can handle decades of hard use. C-FKNL has been operating since the 1940s or 1950s. It’s hauled cargo, landed on rough water, endured Canadian winters, and it’s still airworthy. That’s a testament to the original design.

Float Conversion Works Well

Converting a landplane to floats usually comes with compromises. The floats create drag, reducing speed and fuel efficiency. They add weight, reducing how much cargo you can carry. The airplane becomes harder to handle on the water compared to in the air.

But the Beech 18’s power and size handle these compromises well. With 900 total horsepower (450 per engine), it has enough power to overcome float drag. The sturdy landing gear attachment points adapt to float mounting. The large rudder provides good control for water maneuvering.

What Docking a Beech 18 Actually Looks Like

Years later, I watched YouTube videos of C-FKNL arriving at the Northwest Flying dock—the same dock we’d left from in 2013. Seeing it from outside the airplane gave me new appreciation for what my dad was doing from the pilot seat.

The docking sequence:

Water Taxi

After landing, the pilot keeps the engines running at low power and “taxis” across the water toward the dock area. The sound changes from the roar of takeoff to a steady rumble. The floats settle deeper into the water at slow speed, creating a smooth wake behind the airplane.

Maneuvering

Getting a large twin-engine floatplane into position near a dock requires skill. You can’t steer with a wheel—there’s no wheel.

Wind and water current are constantly pushing the airplane. A Beech 18 has a tall tail that acts like a sail, so even light wind affects where the airplane wants to go.

The pilot has to think ahead—unlike a boat, you can’t just throw it in reverse. You plan your approach so momentum carries you to the right spot just as you’re reducing power.

Final Approach to Dock

In the final 50 feet, the pilot brings power way down. The airplane is mostly coasting now, using its momentum and tiny bursts of power for final adjustments.

This is the hardest part. Too much power and you hit the dock too hard (bad for the floats, bad for the dock, bad for everyone). Too little power and wind pushes you off course and you have to go around and try again.

Docking

Ground crew on the dock use ropes to grab the airplane and guide it to the tie-down position. The pilot keeps the engines running until the airplane is secured—if something goes wrong, you want power available to back away from the dock.

The pilot shuts down the engines and coasts to the dock. They don’t stop immediately—the big radial engines wind down gradually with a descending rumble. Then silence, except for the sound of water lapping against the floats.

Watching this sequence in videos, I realized: Our pilot made it look easy in 2013. It’s not easy. It’s a skill developed over thousands of landings.

The Beech 18 Fleet Still Flying

C-FKNL isn’t the only Beech 18 still working. Dozens are still flying around the world, though their numbers shrink every year.

Why they’re disappearing:

- Age: Most Beech 18s are 60-80 years old now

- Maintenance costs: Keeping old airplanes airworthy gets expensive

- Pilot qualifications: Flying a tailwheel, radial-engine, unpressurized aircraft requires specific training

- Modern alternatives: Newer turbine-powered aircraft are more efficient

- Parts availability: Some components are getting harder to find

Why some survive:

- They’re paid off: No monthly airplane payments

- They’re known quantities: Operators understand their capabilities

- They do the job: For certain missions, they still work well

- Heritage value: Some operators keep them for historical reasons

- Sound: Nothing sounds like twin radials starting up

Northwest Flying Inc. operates two Beech 18s, showing they still see value in the type for their operation. The combination of payload capacity, twin-engine safety, and rugged construction still makes sense for flying passengers and cargo into remote lakes.

What That First Flight Started

That 20-minute flight in C-FKNL when I was eight years old created a passion that will last my whole life. I didn’t understand aviation history or maintenance procedures or piloting technique. I just knew that sitting in that right seat, hearing those radial engines, the flight on that fishing trip felt like the coolest thing in the world.

What happened next:

I started reading about airplanes obsessively. I learned the difference between radial and inline engines, what a tailwheel was, why some planes had floats and others had skis.

I’m not flying C-FKNL. But I love everything about it—older, radial-engine bush planes that have been working in Canada for decades. And every time I hear those engines, I think about that first flight with my dad and grandfather.

Why Old Airplanes Matter

Modern airplanes are objectively better in almost every way. They’re faster, more efficient, more comfortable, and easier to fly. A new turbine floatplane can do everything C-FKNL does while burning less fuel and carrying more weight.

So why does a 70-year-old Beech 18 still matter?

Because it represents a direct connection to aviation history and my family history. The pilots who flew C-FKNL in the 1950s learned their skills during World War II. The pilots flying it now learned from those guys or from people who learned from those guys. That chain of knowledge—passed down through direct training, not just books—is rare.

When Shane Pope teaches a new pilot how to dock a Beech 18 in crosswinds, he’s passing on techniques his father taught him, which his father learned from the generation before. That’s how skills survive.

The airplane itself is a teacher. Logging hundreds of flights in an old radial-engine tailwheel aircraft like the Beech 18 will absolutely build real piloting skill.

Watching C-FKNL arrive at the dock in a YouTube video from 2013—the same year I flew in it—I can now see the skill required. The pilot isn’t fighting the airplane. He’s working with it, using its momentum and characteristics to accomplish something that looks simple but isn’t.

That skill, that knowledge, that connection to aviation history—it only survives if airplanes like C-FKNL keep flying and if experienced pilots keep teaching the next generation.

What the Sound Means Now

I’m in my 20’s now, when I hear twin radial engines start up now—at any airfield, in any video, anywhere—I’m eight years old again, sitting in the right seat of C-FKNL, watching the pilot’s hands on the controls and my dad and grandfather grinning from the back seat.

That sound isn’t just engine noise. It’s family history. It’s aviation heritage. It’s the reason I love this plane.

And somewhere in northern Ontario, C-FKNL is probably flying right now, carrying another family to a remote lake, with maybe an eight-year-old kid in the right seat wondering if this is the coolest thing that’s ever happened to them.

It is.

Want to experience the Beech 18 for yourself? Northwest Flying Inc. still operates C-FKNL and its sister ship from Nestor Falls, Ontario. Book a fly-in fishing trip and ask if you can sit up front. Tell them you want to hear what those radial engines sound like from the right seat.